|

|

| edwardswildman.com | |

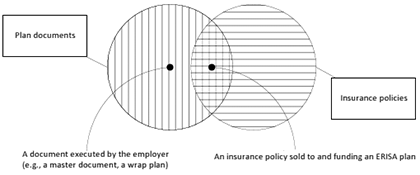

How a State's Anti-Discretion Regulation Might Not Apply to Insured ERISA Plans: the Deemer Clause by Patrick C. Frye (Chicago) An insurer can administer claims for benefits made against an employee-benefit plan that is funded by an insurance policy issued by that insurer. The plan may give the insurer the discretion to interpret its own policy’s terms to determine whether the plan covers a claim for benefits. When an insurer enjoys this delegation of authority, a court can overrule the insurer’s denial of a claim only if the court finds that the administrator abused its discretion. But many states ban an insurer from having the discretion to interpret its policy. When beneficiaries sue to dispute an insurer’s denial of benefits under a plan, they often raise these state bans in an effort to convince a court to substitute its interpretation for the insurer’s. But sometimes the employer delegated the discretion to the insurer in a plan document other than the insurance policy that funds the plan. When that is the case, insurers ought to identify the precise reasons why a state’s anti-discretion regulation does not apply to its administration of claims against an insured plan. This paper notes two arguments insurers should consider when they defend lawsuits for plan benefits, and the delegation of discretion is found in a non-insurance plan document: First, according to its own terms, the regulation may not apply to a non-insurance plan document. Second, the plan is governed by the federal Employee Retirement Income Security Act, better known as ERISA. ERISA has a “Deemer Clause,” which prevents states from regulating plans as if the plans were in the business of insurance. The Deemer Clause therefore overrides any state regulation that might apply to a non-insurance plan document. A Plan and Its Plan Documents An employee-benefit plan is an entity that can sue or be sued under ERISA. 29 U.S.C. § 1132(d). The plan is established by a written instrument, which specifies the basis on which payments are made to and from the plan, and the fiduciary executing the plan terms usually must do so in accordance with the documents and instruments governing the plan. 29 U.S.C. §§ 1102(a) & (b), 1104(a). ERISA does not require that the writings establishing and defining the plan be contained in one document only. Many plans are set forth in multiple documents. Employers that offer multiple plans also often execute a “master document” or a “wrap plan document” to delineate terms and procedures common to all of the employer’s plans. For the plan to afford to pay claims for benefits, employers fund the plan themselves or buy insurance. In a self-funded plan, the employer bears the financial risk of a plan’s costs and expenses in operating the plan and paying claims made against the plan. In an insured plan, the employer funds the plan through an insurance policy. Under this arrangement, the insurer bears the financial risk of making claims payment to the beneficiary directly, while the employer pays a premium for the policy and possibly a fee for the insurer’s services as a claims administrator. Exactly which types of documents comprise the “plan documents” defining the plan may turn on whether the plan is self-funded or insured. The self-funded plan’s plan documents are executed by the employer. For insured plans, plan documents can include the insurance policy and documents employers execute separately, without the insurer. Let us call the latter documents “non-insurance plan documents” because they are issued by the employer and not by the insurer. The figure below depicts two kinds of documents: ERISA plan documents on the left; and insurance policies on the right. Some documents are both, which is why the circles overlap. But some plan documents are not insurance policies, so they fall within the circle on the left and not within the circle on the right. These are the non-insurance plan documents.

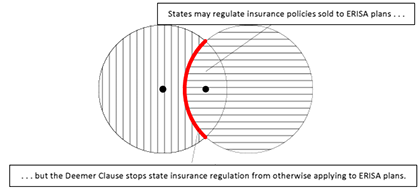

In insured plans, an insurance policy can pull double-duty, both funding claim payments and defining plan benefits. A non-insurance plan document is unnecessary and exists only when an employer opts to create one. Many insured plans are documented only by an insurance policy. Further, in insured plans that include a non-insurance plan document, the plan’s benefits are usually defined by the insurance policy and no other plan document. Discretionary Clauses and Anti-Discretion Regulations ERISA permits plans to decide the standard by which a court can review a plan’s denial of benefits. Under de novo review, which applies if the plan is silent, the court can second-guess the claims administrator’s interpretation of the plan’s terms. Under review for abuse of discretion, the court defers to the administrator’s interpretation so long as it has at least some reasoned justification, however unconvincing. To change the court’s standard of review from de novo to abuse of discretion, plans often delegate discretion to their claims administrator through a “discretionary clause.” One example of this kind of clause is: “The claims administrator has sole discretionary authority to determine your eligibility for benefits and to interpret the terms and provisions of the policy. Benefits under these Plans will be paid only if the claims administrator decides, in its discretion, that you are entitled to a benefit.” Discretionary clauses encourage employers to offer plans, because these clauses limit the unpredictability of a plan’s future costs. Because of these clauses, the plan avoids courts’ possibly unexpected, inaccurate, or inconsistent interpretations of the plan documents. In comparison to claims decisions subject to de novo review, the claim administrator can make interpretations that are more uniform and predictable and render a decision that is closer to final. Interpreting the plan is a fiduciary duty, and ERISA permits the plan to delegate this authority to an insurance company. 29 U.S.C. §§ 1102(b) & (c), 1105(c). As part of this delegation, the plan may grant the insurer the discretion to interpret the plan’s terms. In most insured plans, the benefits are commonly defined only in the insurance policy issued by the insurance company that serves as the plan’s claims administrator. But imagine if an insurance company would grant itself the discretion to interpret its policies, even those sold directly to the average consumer. Its denials of coverage would be upheld absent an abuse of discretion, whereas in the normal coverage litigation, the court would give the insurer’s decision no deference and construe an insurance policy’s ambiguous language in favor of the insured. Some states have banned insurance companies from giving themselves this power. California, New York, and Illinois (among others) prohibit discretionary clauses in insurance contracts. Many of these anti-discretion regulations are based on the NAIC model, which reads: “No policy, contract, certificate or agreement offered or issued in this state by a health carrier to provide, deliver, arrange for, pay for or reimburse any of the costs of health care services may contain a provision purporting to reserve discretion to the health carrier to interpret the terms of the contract, or to provide standards of interpretation or review that are inconsistent with the laws of this state.” In litigation contesting an insurer’s denial of plan benefits, a beneficiary may argue that a state ban on insurance discretionary clauses should permit a court to review the insurer’s denial without any deference to the insurer’s interpretation of the plan. However, if the delegation of discretion is found in the employer’s non-insurance plan document, the state’s anti-discretion regulation might not apply because not all such regulations reach a non-insurance plan document. Moreover, ERISA’s Deemer Clause, 29 U.S.C. § 1144(b)(2)(B), prevents any state regulation from applying to a non-insurance plan document. The Anti-Discretion Regulation by Its Own Terms May Not Apply to a Non-Insurance Plan Document As a threshold matter, not all anti-discretion regulations purport to reach all ERISA plan documents. Some states’ regulations explicitly exempt policies sold to an ERISA plan. These regulations should not impair the insurer’s discretion in serving as a plan’s claims administrator. In some other states, the regulations apply only to those discretionary clauses found in policies issued by insurance companies. Illinois’s, for example, concerns any “policy, contract, [and the like] offered or issued in this State, by a health carrier.” 50 Ill. Admin. Code § 2001.3. Employers are not carriers, and it is the employer and not the insurer that established the plan and executes the non-insurance plan document. This limit on the Illinois regulation’s reach has not been appreciated by Illinois courts reviewing the discretion delegated in an insured plan’s non-insurance plan document. These courts analyzed whether the plan document was a policy or similar instrument and whether the insurer that funded the plan was a “health carrier.” Perhaps the courts were correct to conclude that plans are insurance and the insurers that fund them are health carriers. But these are not the arguments to make. The critical question is whether the non-insurance plan document is “offered or issued . . . by a health carrier.” It is not. State Regulation Is Deemed Not to Apply to a Non-Insurance Plan Document If a state anti-discretion regulation would apply to a non-insurance plan document, then ERISA prevents that regulation from actually applying. ERISA “supersede[s] any and all State laws insofar as they may now or hereafter relate to any employee benefit plan.” 29 U.S.C. § 1144(a). ERISA’s “Savings Clause” commands that “nothing in [ERISA] shall be construed to exempt or relieve any person from any law of any State which regulates insurance . . . .” Id. § 1144(b)(2)(A). For a law to be saved as an insurance regulation, it must be specifically directed towards the insurance industry – namely, insurers with respect to their insurance practices. While an anti-discretion regulation is saved from preemption, ERISA’s “Deemer Clause” forbids the regulation from applying to an ERISA plan and, therefore, its non-insurance plan documents. The Deemer Clause states: 29 U.S.C. § 1144(b)(2)(B). The Savings Clause permits a state to regulate an insurance policy even if it is a plan document, while the Deemer Clause will not permit any such regulation to reach a non-insurance plan document. A state’s insurance regulation may affect a plan only if it is funded by insurance. It therefore cannot affect a self-funded plan at all. The regulation’s effect on an insured plan is indirect only: by limiting the policies insurers can sell, states limit what policies plans can buy. The following diagram illustrates this point:

Thus when a non-insurance plan document delegates discretion to the insurer as the insured plan’s claims administrator, the state’s anti-discretion regulation cannot override the discretionary clause. The Deemer Clause is commonly misconceived as not applying at all to insured plans. Indeed, in at least one lawsuit where a non-insurance plan document delegated discretion, the insurer conceded that the Deemer Clause was irrelevant because the plan was insured, and the court refused to defer to the insurer’s discretion. The insurer’s concession was unwarranted. The Deemer Clause itself makes no distinction between self-funded plans and insured plans. It bars direct state regulation of plans, and an insurer would be remiss to overlook the Deemer Clause if the insurer has been delegated discretion by a non-insurance plan document. Why State Regulation Should Not Reach Non-Insurance Plan Documents A court may need convincing that good policy is served in enforcing an ERISA non-insurance plan document that permits an insurer to do what it cannot do pursuant to its own insurance policies. It is best to distinguish between insurance policies that double as plan documents, on the one hand, and non-insurance plan documents, on the other, because when the insurer administers a claim for plan benefits, it acts as an agent of the plan. It must obey the terms of that plan, subject to ERISA. In bringing a lawsuit contesting a denial of benefits, the beneficiary typically seeks to recover benefits under the “terms of his plan.” 29 U.S.C. § 1132(a). If in the non-insurance plan document, the employer makes the benefits owed dependent on the administrator’s discretion, then the insurer is fulfilling the employer’s direction by exercising the discretion delegated to it. But if the employer has not delegated discretion in a non-insurance plan document, the employer might not have made any decision at all about the administrator’s discretion. In that case, the workforce gets the benefit of all insurance regulation of the policy sold to fund the plan, including a court’s de novo review of a denial of a claim. There is no reason why an insured plan’s insurer cannot have the discretion that self-funded plans’ employers enjoy. Supposedly, an insured plan’s insurer has a conflict of interest in denying the claims it might pay, but this explains nothing. An employer of a self-funded plan may appoint itself as the claims administrator and delegate itself discretion. The self-funded plan's claims administrator may seem to have a conflict of interest, but the courts defer to the discretion the employer exercised in denying claims. By the same token, the insured plan's claims administrator may seem to have a conflict of interest, but this supposed conflict should not justify preventing an insurer from having – at the employer’s direction – the very same discretion. The employer need not establish any benefit plan at all. Permitting non-insurance plan documents to override a state’s insurance regulation keeps control of the plan with the employer. If an employer can control a plan, it can predict the expenses of having a plan. Making the plan’s expenses predictable encourages employers to offer plans in the first instance and to offer plans with better benefits than they might have had in the face of more uncertain liabilities. Logically, it would be a good practice for an employer establishing insured plans to draft its own plan document in addition to the insurance policy. But this practice would be for naught if insurers do not effectively defend it in the courts. Therefore, an insurer delegated discretion by employers should, where advisable, argue that the anti-discretion regulation by its own terms does not reach a non-insurance plan document, and should always argue that the Deemer Clause does not permit a state regulation to apply to a non-insurance plan document. ERISA commands that the courts honor an employer’s decision to delegate discretion to an insurer. Contact

| |

|

|